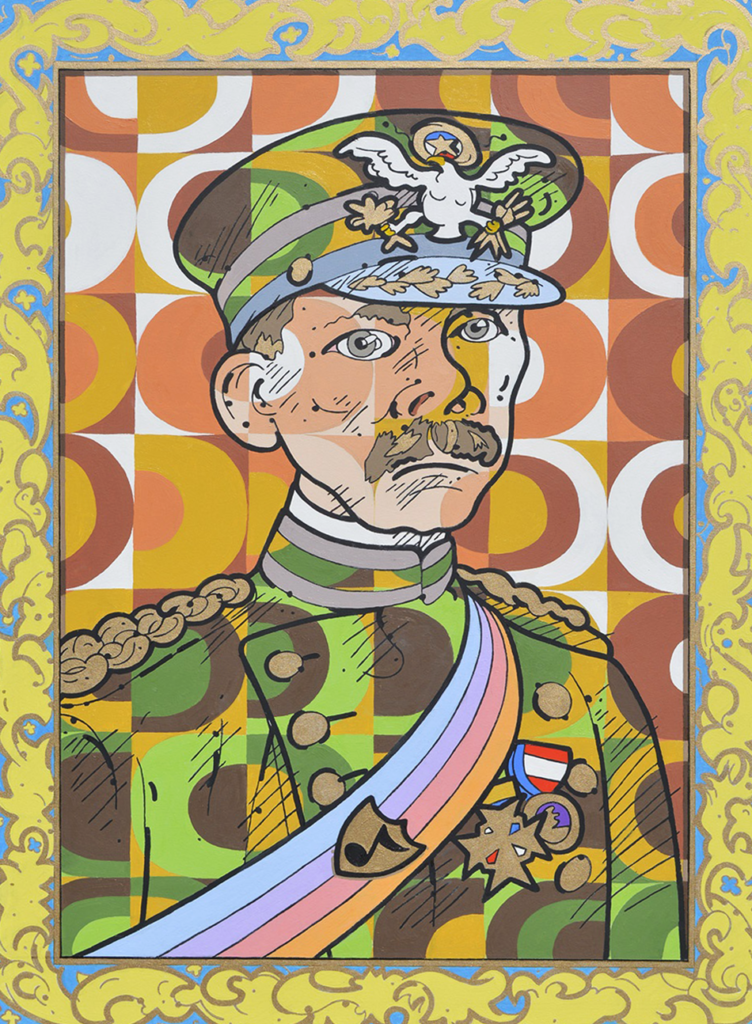

Ready, Mr. Muzak?: portrait of Maj. Gen. George Owen Squier

Ready, Mr. Muzak?: portrait of Maj. Gen. George Owen Squier

Material: Oil on canvas

Size: 48×36

Year: 2020

If you want to make beautiful music, you must play the black notes and the white notes together. – Richard Nixon

Long, long ago in a universe far, far away, before the folk music scare of the early 1960s was even a twinkle in Bob Dylan’s eye, and even before the birth of rock-and-roll, background music was invented. Easy Listening. Elevator music. Telephone on-hold music. And we have General George Owen Squier to thank for it. Thanks a lot, George.

General Squier invented telephone multiplexing in 1910 and acquired patents in 1922 for methods of distributing signals over existing electrical lines. He saw the potential for this trick to deliver music to subscribers, without the need for a radio. Radio caught up to him in the 1930s, so he concentrated his efforts on delivering music to commercial customers. (All this happened in Cleveland, the town that takes radio seriously.) In 1934, Squier named his company Muzak, because his product was music and he liked the name Kodak. No other reason. By then he’d learned manipulative musical tricks to ease worker-listener stress and to encourage productivity, as well to motivate shoppers. He next began to record his own music, which became known as Muzak.

He was accused of brainwashing the public in the 1950s, but who wasn’t? In the 60s and 70s, demand for Muzak became so huge that it found its way back into our most personal and holy sanctum, the private home.

Major General George Owen Squier was buried when he died (not before, though some were tempted) beside his mentor and protégé Major Uptick, in Arlington National Cemetery, which makes him John F. Kennedy’s equal. But not JFK’s confederate – Robert E. Lee was the confederate, and the man who generously donated his vast front yard to become our nation’s most prestigious boneyard. We thank you for this, Bobby.